Schedule I drugs are the most dangerous and Schedule V drugs are the least. If your drug arrest involves Schedule I or Schedule II drugs, you have an increased chance of being charged with a felony offense. If you are found guilty, you can be sentenced based on Pennsylvania’s mandatory minimum sentencing laws that apply to all scheduled drugs.

- Schedule II drugs require professional intervention from the pharmacist (e.g. Patient assessment and patient consultation) prior to sale. Schedule III drugs must be sold in a licensed pharmacy, but can be sold from the self-selection area of the pharmacy. Unscheduled drugs can be sold without professional supervision, from any retail outlet.

- Drugs.com provides accurate and independent information on more than 24,000 prescription drugs, over-the-counter medicines and natural products. This material is provided for educational purposes only and is not intended for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Data sources include IBM Watson Micromedex (updated 7 Dec 2020), Cerner Multum™ (updated 4 Dec 2020), ASHP (updated 3 Dec 2020.

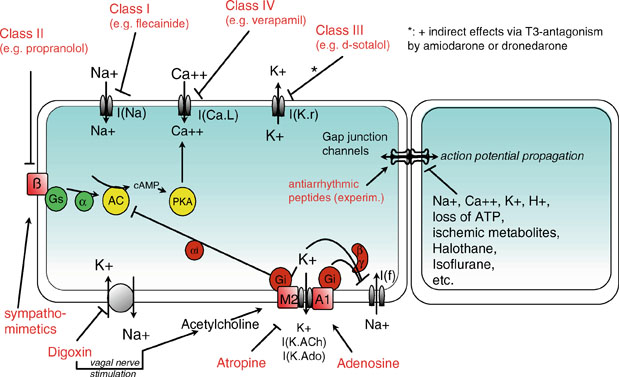

- Class II agents. Class II agents are conventional beta blockers.They act by blocking the effects of catecholamines at the β 1-adrenergic receptors, thereby decreasing sympathetic activity on the heart, which reduces intracellular cAMP levels and hence reduces Ca 2+ influx. These agents are particularly useful in the treatment of supraventricular tachycardias.

Health Canada and the National Association of Pharmacy Regulatory Authorities (NAPRA) both have roles related to drug scheduling in Canada. These roles are separate and distinct, with each organization performing specific functions within the drug scheduling process.

Health Canada

Health Canada has the authority and responsibility to authorize health products (e.g. drugs, natural health products, medical devices) for sale in Canada. It is the responsibility of Health Canada to evaluate the safety, efficacy and quality of health products and to provide an authorization for sale in Canada. Only with an authorization and/or licence from Health Canada would a manufacturer be permitted to sell a health product in Canada.

During its review of a particular health product, Health Canada will also classify the health product into various types, such as medical device, natural health product or drug product. Health Canada will further classify drug products into additional categories, such as controlled substance, biologic product, prescription drug, or non-prescription drug. This can occur by placing a drug on the schedules that are part of federal laws and regulations and thus is sometimes called drug scheduling. This is a separate and distinct process from the NAPRA drug scheduling process, which is explained in the next section.

During its evaluation of the safety, efficacy and quality of each drug product, Health Canada will determine whether or not a prescription is required for sale of the drug in Canada. Drugs that Health Canada has determined require a prescription for sale in Canada are listed on the Health Canada Prescription Drug List (PDL) or in the schedules to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act and its regulations. Once Health Canada classifies a drug as requiring a prescription for sale, then it requires a prescription for sale in all of Canada.

More information on Health Canada’s role in drug scheduling and in the authorization of health products for sale in Canada can be found on the Health Canada website.

NAPRA and the National Drug Schedules

NAPRA’s role in the drug scheduling process occurs after Health Canada has authorized a drug for sale in Canada and determined whether the drug requires a prescription for sale. NAPRA does not have any role or authority in the authorization of new health products for the Canadian market and does not review products that have been classified as requiring a prescription by Health Canada.

While the federal government determines certain conditions of sale, such as the need for a prescription, provincial/territorial governments have the ability to further specify the conditions of sale of drug products. Prior to 1995, each province and territory had its own system for determining the conditions of sale for non-prescription drugs in Canada, leading to wide variability in the way drugs were sold across Canada.

In 1995, NAPRA’s members, the pharmacy regulatory authorities across Canada, endorsed a proposal for a national drug scheduling model, to align the provincial/territorial drug schedules so that the conditions of sale for drugs would be more consistent across Canada. This harmonized national model is administered by NAPRA and is called the National Drug Schedules (NDS) program.

All of the provinces and territories, except Quebec, have adopted the National Drug Schedules in some manner. The NDS come into force in each province/territory through provincial/territorial legislation. In some cases, the National Drug Schedules are directly referenced in provincial/territorial legislation, while in others additional actions are required to implement the NDS recommendations. More information on the implementation of the National Drug Schedules across Canada is available on the NAPRA website.

In general, the National Drug Schedules capture drugs that have been authorized for sale and classified as non-prescription by Health Canada. Other products approved by Health Canada (e.g. natural health products, medical devices) are outside the scope of the program and are not considered products for scheduling within the National Drug Schedules.

The NDS program consists of three schedules and four categories of drugs. Schedule I drugs require a prescription for sale. Schedule II drugs require professional intervention from the pharmacist (e.g. patient assessment and patient consultation) prior to sale. Schedule III drugs must be sold in a licensed pharmacy, but can be sold from the self-selection area of the pharmacy. Unscheduled drugs can be sold without professional supervision, from any retail outlet.

The drug scheduling process usually begins when NAPRA receives a drug scheduling submission from a pharmaceutical company. The National Drug Scheduling Advisory Committee is an expert advisory committee that reviews the drug scheduling submissions received by NAPRA and formulates drug scheduling recommendations. There is a specific process that must be followed during each drug scheduling review, which is outlined in NAPRA’s By-law No. 2 and Rules of Procedures. The model for making drug scheduling recommendations embodies a “cascading principle” in which drugs are assessed against specific scheduling factors. A drug is first assessed using the factors for Schedule I. Should sufficient factors apply, the drug remains in that Schedule. If not, the drug is assessed against the Schedule II factors, and if warranted, subsequently against the Schedule III factors. Should the drug not meet the factors for any schedule, it becomes “Unscheduled” (the fourth category).

According to this cascading principle, it is possible, although rare, for NAPRA to place a product in Schedule I that Health Canada has classified as a non-prescription product. This could occur because of the NAPRA policy for drugs not reviewed, which places drugs into Schedule I until they are reviewed, or because of a range of factors considered by the expert advisory committee when applying the cascading drug scheduling model. As described above, the provinces and territories can add additional conditions of sale for non-prescription drugs, but can never be less restrictive than federal legislation.

Once the National Drug Scheduling Advisory Committee has reviewed a particular drug, it will make an interim drug scheduling recommendation. A 30-day consultation period follows, after which the NAPRA Board of Directors will make a final scheduling recommendation. The National Drug Schedules are then amended and the final recommendation is implemented according to the rules in each particular province or territory.

A drug class is a set of medications and other compounds that have similar chemical structures, the same mechanism of action (i.e. binding to the same biological target), a related mode of action, and/or are used to treat the same disease.[1][2]

In several dominant drug classification systems, these four types of classifications form a hierarchy. For example, the fibrates are a chemical class of drugs (amphipathic carboxylic acids) that share the same mechanism of action (PPAR agonist) and mode of action (reducing blood triglycerides), and that are used to prevent and treat the same disease (atherosclerosis). Conversely, not all PPAR agonists are fibrates, not all triglyceride lowering agents are PPAR agonists, and not all drugs used to treat atherosclerosis are triglyceride-lowering agents.

Class 1 2 3 Circuits

A drug class is typically defined by a prototype drug, the most important, and typically the first developed drug within the class, used as a reference for comparison.

Comprehensive systems[edit]

- Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC) - most widely used. Combines classification by organ system and therapeutic, pharmacological, and chemical properties.

- Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) - includes a section devoted to drug classification

Chemical class[edit]

Class 1 2 3 Devices

This type of categorisation of drugs is from a chemical perspective and categorises them by their chemical structure. Examples of drug classes that are based on chemical structures include:

Mechanism of action[edit]

This type of categorisation is from a pharmacological perspective and categorises them by their biological target. Drug classes that share a common molecular mechanism of action by modulating the activity of a specific biological target.[3] The definition of a mechanism of action also includes the type of activity at that biological target. For receptors, these activities include agonist, antagonist, inverse agonist, or modulator. Enzyme target mechanisms include activator or inhibitor. Ion channel modulators include opener or blocker. The following are specific examples of drug classes whose definition is based on a specific mechanism of action:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug − cyclooxygenase inhibitor

- Statin – HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor

Mode of action[edit]

This type of categorisation of drugs is from a biological perspective and categorises them by the anatomical or functional change they induce. Drug classes that are defined by common modes of action (i.e. the functional or anatomical change they induce) include:

Class 1 2 3 Drugs

- Diuretic or Antidiuretic

- Inotrope (positive or negative)

- Chronotrope (positive or negative)

Therapeutic class[edit]

This type of categorisation of drugs is from a medical perspective and categorises them by the pathology they are used to treat. Drug classes that are defined by their therapeutic use (the pathology they are intended to treat) include:

Amalgamated classes[edit]

Some drug classes have been amalgamated from these three principles to meet practical needs. The class of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is one such example. Strictly speaking, and also historically, the wider class of anti-inflammatory drugs also comprises steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. These drugs were in fact the predominant anti-inflammatories during the decade leading up to the introduction of the term 'nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs'. Because of the disastrous reputation that the corticosteroids had got in the 1950s, the new term, which offered to signal that an anti-inflammatory drug was not a steroid, rapidly gained currency.[4] The drug class of 'nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs' (NSAIDs) is thus composed by one element ('anti-inflammatory') that designates the mechanism of action, and one element ('nonsteroidal') that separates it from other drugs with that same mechanism of action. Similarly, one might argue that the class of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARD) is composed by one element ('disease-modifying') that albeit vaguely designates a mechanism of action, and one element ('anti-rheumatic drug') that indicates its therapeutic use.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)

- Disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD)[5]

Other systems of classification[edit]

Other systems of drug classification exist, for example the Biopharmaceutics Classification System which determines a drugs' attributes by solubility and intestinal permeability.

Legal classification[edit]

- For the UK legal classification, see Drugs controlled by the UK Misuse of Drugs Act

- For the US legal classification, see Controlled Substances Act § Schedules of controlled substances

- Pregnancy category is defined using a variety of systems by different jurisdictions

References[edit]

- ^Mahoney A, Evans J (2008). 'Comparing drug classification systems'. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings: 1039. PMID18999016.

- ^World Health Organization (2003). Introduction to drug utilization research(PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. p. 33. ISBN978-9241562348.

- ^Imming P, Sinning C, Meyer A (Oct 2006). 'Drugs, their targets and the nature and number of drug targets'. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 5 (10): 821–34. doi:10.1038/nrd2132. PMID17016423.

- ^Buer JK (Oct 2014). 'Origins and impact of the term 'NSAID''. Inflammopharmacology. 22 (5): 263–7. doi:10.1007/s10787-014-0211-2. hdl:10852/45403. PMID25064056.

- ^Buer JK (Aug 2015). 'A history of the term 'DMARD''. Inflammopharmacology. 23 (4): 163–71. doi:10.1007/s10787-015-0232-5. PMC4508364. PMID26002695.

External links[edit]

- 'Drug names and classes'. PubMed Health. United States National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2015-11-07.

- 'Information by Drug Class'. Drug Safety and Availability. United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2015-11-07.